I read a lot about AI — but not about how people actually use it

I read a lot of stuff about AI all over the place, but what I rarely read about is how people are actually using it, in practical terms. Everybody talks about their projects, but almost nobody describes the processes and the day-to-day tricks that help them finalize those projects with accuracy and success.

Maybe I’m not the most reliable person to make such a statement. There are probably communities that discuss this extensively. But I’m the average guy when it comes to this topic: learning by doing and checking three or four sources regularly (YouTube being one of them).

That said, the work environments I’ve been part of recently have been my best source of knowledge when it comes to using AI tools. One thing I’ve noticed is that most people I interact with are learning to use these tools in very different ways. It’s a deeply personal approach — one that reflects how we deal with many other aspects of life.

There’s the methodical AI user, the scared one, the spontaneous one, the skeptical one, the addicted one. Then there are the philosophies:

the doomsday thinker who believes robots will take over the world within six months;

the optimist who thinks cancer will be eradicated soon;

the world conqueror who wants to develop chips to enhance intelligence and learn kung-fu like Neo in The Matrix.

And so on, and so forth.

What I want to share here are four super-intuitive tips — plus two extra ones — that are genuinely helping me every day to crack and solve problems that felt extremely complex and time-consuming before AI entered the picture.

This is not a guide about AI projects or future promises, but about practical AI use in daily work, learning by doing, and building workflows that actually save time.

And the best part? You can apply them immediately and start improving your current (and future) opportunities right now.

Tip n. 1 — Treat AI like a smart collaborator, not a magic box

I’ve seen friends and colleagues share results obtained from a single prompt — no exchange further exchange with the AI tool, just one prompt. Sure, maybe Sam Altman is capable of writing a prompt so perfect that no follow-up is required.

But most of us absolutely need to dig into the results of our prompts — until all the dark corners, potential misleading information, and questionable sources are double, triple, quadruple-checked.

I’ve noticed that when I carefully read what AI returns — like actively listening to a colleague, a good friend or a partner — the follow-up questions improve exponentially, and the quality of the next outputs is on a completely different level.

Tip n. 2 — Improve your prompts before execution

If I’m not mistaken, tools like Copilot already offer an agent that does this by default. But you can easily create your own prompt that says:

“Please, correct and improve this prompt: [prompt here]”

And before you say anything about the word please: I say “good morning” to my AI tools every day. You never freaking know! But I’ve watched too many sci-fi movies…

Tip n. 3 — Use screenshots to learn tools faster with AI

Let’s say you have a blog like mine and you want to use Google Analytics (GA) to improve your keywords, understand your audience, and so on.

(Things that — as I’ve said many times across my posts — I don’t do for my personal blog. This is a hobby, not a validation machine, and I refuse to enter the paranoia-wheel of likes, comments, subscribers, and views.)

But let’s pretend you do want to do that — and you’ve never used GA before.

If you go through the official GA guidelines, there’s so much content out there that before you even start using the tool, your head is already spinning.

So what do you do?

You create an account (easy enough), and then for any doubt you have — no matter how silly — you just take a screenshot and ask ChatGPT, Copilot, Perplexity, or whatever you use:

“I don’t understand what to do next. Please explain concisely, step by step, in simple terms.”

You’re welcome. You’ll can come back to thank me later.

Tip n. 4 — Use AI to summarize and explore the web efficiently

Give AI the websites you want to summarize or explore faster.

For example:

“Crawl website www.xyzittttyb.co.uk and give me the most relevant links related to xyz.”

It’s a dumb example, obviously — but you can crawl websites for much more exciting things than that.

Extra tip — Clean, refine, and share for feedback

I’ve heard people say they want to keep their prompts and results secret so others don’t copy their ideas 🤦🏽♂️… Some people operate on levels of confidence and delusion that are simply beyond my reach. They think they’re freaking Einstein or Tesla, I don’t know.

Guys, the era where isolated geniuses existed is over. Accept it.

Knowledge is now accessible to anyone with an internet connection, curiosity, and enough time to play with AI tools and develop skills. The more you share, the more you learn: people give feedback, you discover your flaws, and you improve.

Observe what others do. Be humble.

Follow the Socratic idea: “To know is to know that you know nothing.”Doors will keep opening new paths constantly.

Think you know everything, and your horizon will be as wide as the space between your ears.

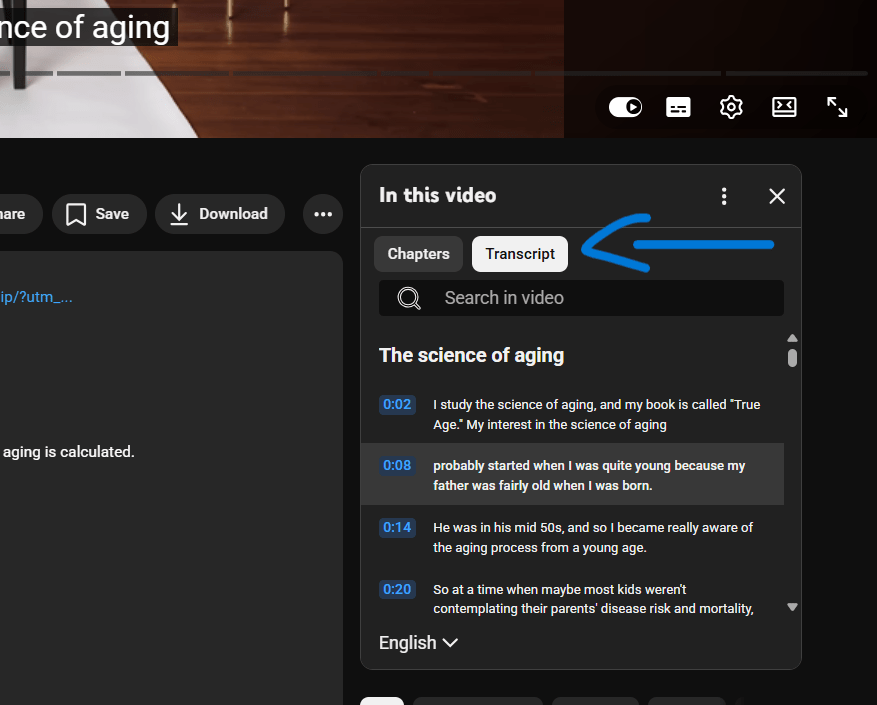

Extra tip n. 2 — Summarize YouTube videos

Just copy-paste the transcript and ask AI to summarize it. Hours of few in a few minutes read.

That’s it. No magic. Just leverage what’s already there.

Bottom line

Practical AI use isn’t about better tools — it’s about better questions, better iteration, and treating AI as part of your daily workflow instead of a shortcut machine.

It doesn’t require genius-level prompts, secret tricks, or futuristic visions. It rewards curiosity, patience, iteration, and humility. Treat it like a conversation, let it help you think more clearly, and don’t be afraid to share what you learn. The real advantage isn’t knowing more — it’s learning faster, together.