In the last few decades, thanks especially to the internet and a more globalized world, a segment of Earth’s citizens has progressively benefited from a borderless reality, allowing them to move and establish themselves almost anywhere they desire — a trend exacerbated following the COVID pandemic.

The reasons for such a choice are many, depending on the profession one exercises, a search for better living conditions, a drive to live differently according to rules and cultural norms that better resonate with them, and so forth. This practice has given rise to enticing titles that the privileged among us proudly embrace: globe trotters, digital nomads, expats, remote workers.

In many cases, though, this decision to move somewhere else has been driven by a simple impulse to explore a different corner of the world for a short period of time, only to then move on to another, making this some sort of appealing practice. There are many documentaries available online of influencers, for example, going somewhere like India only to criticize the way other cultures live and leave with a pros and cons list to share with their audience, disregarding the long-term consequences of their actions.

Lately, I have been reflecting on whether this last category of professionals who wander around the globe deserves a more specific title with a connotation that fits this type of mindset.

Today, we are more aware that the privilege of some comes at the expense of others, often decreasing the quality of life for local communities. Perhaps we’ve always known this, but we are now more mature and collectively prepared to take responsibility for our actions. Despite this, no term has been coined to properly define this category of nomads. This has led me to question whether a more nuanced vocabulary might better highlight the less glamorous consequences of some people who take advantage of global professional mobility. One term I’ve been pondering is globalist jackals.

The existing terms are usually associated with the appealing aspects of global mobility: cultural depth fostered by living in different parts of the world; the boost to economies through spending power and new businesses in areas with lower living costs; the flexibility of work environments; and inclusivity. These and many other aspects have served as catalysts for global change and innovation.

Unfortunately, there is another side to the coin.

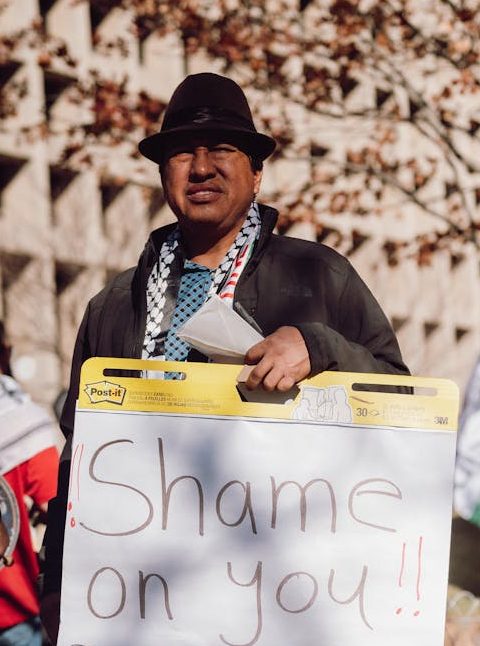

What I would call globalist jackals, in particular, drive up living costs in the areas where they relocate. Their demand for short-term rentals reduces housing availability for residents. They displace communities, contributing to over-tourism, disrupting local cultures, and eroding traditional ways of life, leaving some communities feeling exploited or undervalued.

Moreover, individuals benefiting from global mobility who genuinely wish to integrate and adapt to local customs may face misjudgment or unjust accusations, being lumped together with those who move on to their next destination without meaningful interaction or pondering their choices with reasons beyond the drive to “discover the world.”

Legal gray areas are created and exploited by individuals with selfish intentions, with little to no regard for local community needs. For example, it’s known that governments struggle to tax digital nomads who earn abroad while utilizing local resources, even though this varies greatly by country and specific tax treaties.

It has also been reported that what I would define as globalist jackals exacerbate inequalities, widening the gap between those with access to technology, education, and global mobility versus those without.

While there are many other factors that could justify coining the term globalist jackals, it’s crucial to recognize the dangers of using such pejorative terms indiscriminately. Doing so risks fueling discriminatory and even racist narratives.

The debate around the terminology we use to describe global professionals underscores the need for accountability and awareness in a world where profiting from mobility by choice, and not by survival-oriented need or duty, is both a privilege and a responsibility. As global citizens, we must understand what impact our ambitions have on others, acknowledging that consequences may take time to arise and often unfold in unpredictable ways.

This is a speculative and reductive take on a much broader and more complex topic, one that has been researched and discussed in much greater depth. So, please take my perspective with a grain of salt. I am curious to hear your thoughts. Have you previously reflected on this topic, specifically the glamorous terminology used to define this trend? Does the term globalist jackal make sense? What other terms would you suggest for discussing this phenomenon?